In a world where information is just a tap away, it’s easy to overlook the rigorous research that powers these rapid results. The lasting impact of long-term research was celebrated recently at A Taste of Research: Enduring Discoveries, a showcase hosted by the University of Regina in honour of its 50th anniversary and as part of the Chancellor’s Community lecture series.

The audience explored the University’s ongoing research through eight-minute presentations by four faculty members—each sharing insights into their enduring projects. Between each faculty talk, graduate students who previously won Three-Minute Thesis (3MT) competitions captivated the crowd with three-minute presentations, using only one static slide.

This inspiring evening illustrated how research evolves across generations, bringing lasting value to the University, the community, and beyond. Read on to discover each presentation in the order it was given.

Heather Hadjistavropoulos kicked off the evening with her presentation on internet-delivered therapy. A psychology professor, she leads the Wellbeing Innovation Lab and is the founder and executive director of the University’s Online Therapy Unit.

Hadjistavropoulos told the audience that despite mental-health issues being widespread and often debilitating, they often go untreated. Her presentation focused on the long-standing research that she and her team at the University are doing using internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy (ICBT) as an effective way to treat conditions such as depression, anxiety, and alcohol misuse. She highlighted for the crowd how online ICBT is making mental-health care more accessible.

Drawing from extensive research that has shaped its clinical use, she explained how ICBT is unlocking new doorways to mental-health services and reaching those who need support – virtually and cost-effectively.

Andy McLennan, supervised by Dr. Thomas Hadjistavropoulos, is a clinical psychology PhD student at the University of Regina. In his three-minute presentation, he explained that there are many tools that claim to assess pain in older adults with dementia, assuming this population needs a unique approach—but said no one has really tested this idea.

McLennan said his study took a fresh look, comparing specialized tools, such as one used for younger people with cognitive issues. By observing videos of older adults with severe dementia, his study checked each tool’s ability to pick up on pain behaviours during quiet moments and physical exams. Surprisingly, McLennan said all tools—specialized or not—worked well at spotting pain. These findings challenge the notion that different pain tools across age groups are needed, suggesting that one approach may work for many.

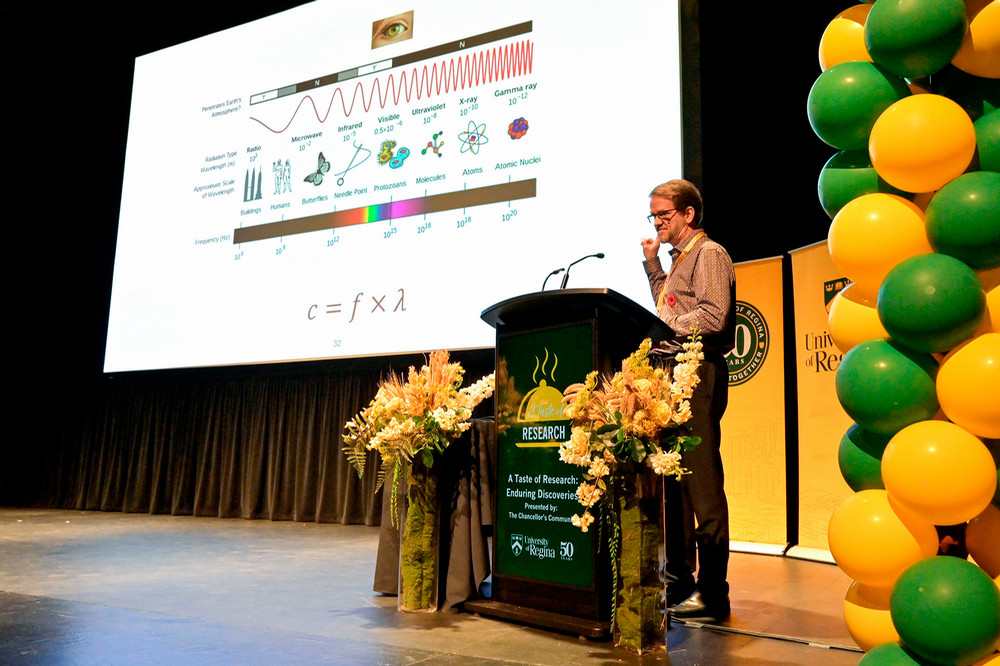

Dr. Zisis Papandreou is a physics professor and principal investigator of subatomic physics projects at the University of Regina, where he specializes in developing advanced nuclear physics instrumentation. He told the crowd that for decades he has been using powerful tools—such as particle accelerators and advanced detectors—to delve into the mysteries of the universe. In an easy-to-understand way, he explained how these sophisticated machines serve as super microscopes and atom smashers, allowing him and his colleagues to explore the fundamental building blocks of matter at the atomic level to advance our fundamental understanding of the world around us.

Papandreou explained how the University of Regina’s physics department has been a leader in developing and deploying these technologies, making significant contributions to national and international accelerator facilities across three continents for more than 40 years. Papandreou’s talk highlighted the journey of innovation that has established the University’s prominent role in detector design, construction, and experimental nuclear physics. He highlighted how his efforts led to the launch of a multi-million-dollar applied physics program at the U of R, where nuclear imaging techniques are now being harnessed to solve real-world problems in agriculture and soil cleanup.

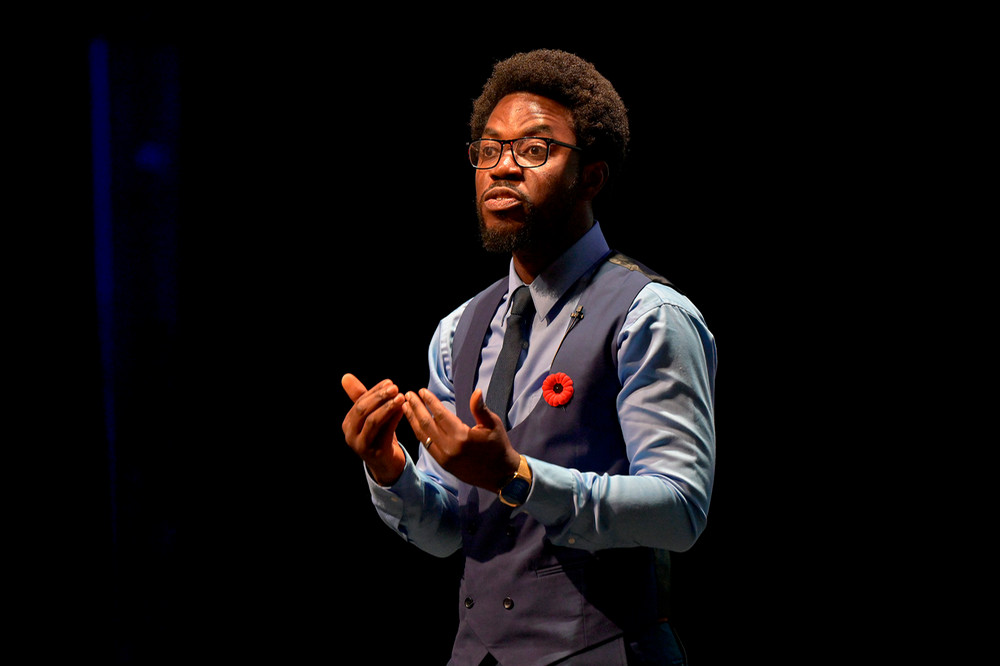

Kwaku Ayisi is a PhD candidate at the Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy and is supervised by the U of R’s Dr. Cheryl Camillo. His talk explained that in Canada, Indigenous children make up just 7.7 per cent of all kids, but account for nearly 54 per cent of those in government child-welfare programs, a long-standing concern for Indigenous communities and organizations. He told the audience that in 2020, Cowessess First Nation in Saskatchewan became the first in Canada to implement its own child welfare law, the Miyo Pimatisowin Act, which was done under federal Bill C-92, which aims to protect Indigenous children from government care and improve their overall well-being.

In his captivating three-minute talk, Ayisi discussed how Cowessess developed its child-welfare policies through Keeoukaywin, or "The Visiting Way," a culturally meaningful and decolonized approach. Ayisi talked about how the Miyo Pimatisowin Act has successfully kept all Cowessess children out of government care by focusing on community driven prevention strategies, including cultural teachings, parenting classes, and the guidance of Cowessess grandmothers to support the well-being of children and families.

Dr. Shannon Holmes, an associate professor of theatre, is a performer, theatre-maker, vocal coach, pedagogue, and researcher. Her presentation detailed how performance autoethnography is a research method that uses the performer's own experiences and body to explore and explain culture and society. As an artist and scholar who works with voice, Holmes said this makes her the focus of her research, both as the one doing the research and as the subject of the study.

In this presentation, Holmes discussed how she created The Crook of Your Arm, a solo performance, with voice and movement, and then, accompanied by cello, performed through song and storytelling a moving excerpt from the longer piece that grew out of her research that explores themes of memory, family, and loss.

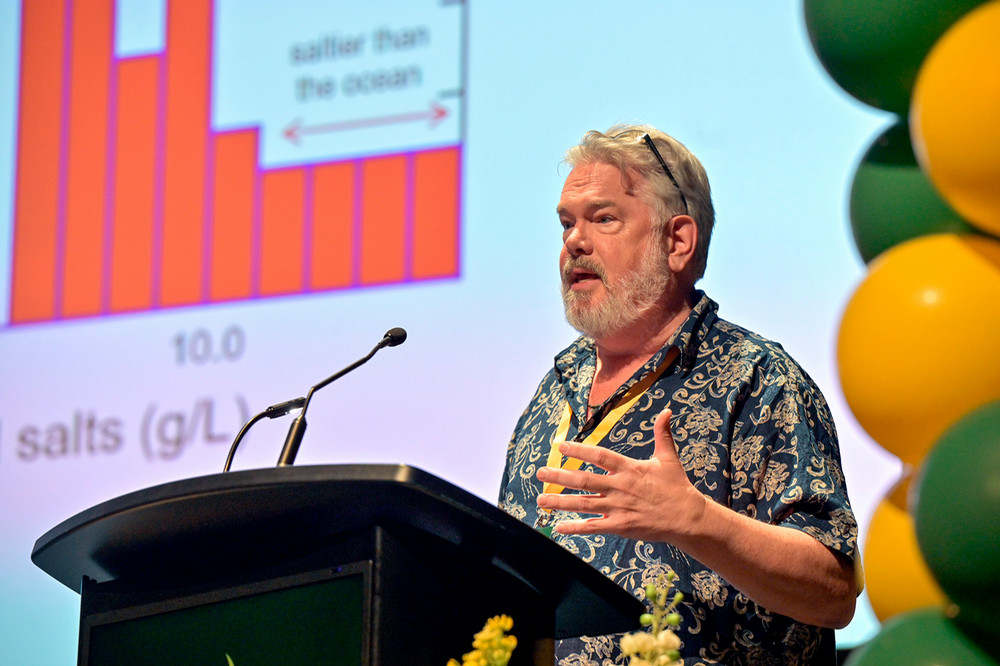

Dr. Peter Leavitt is a biology professor and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, the U.K. Royal Society of Biology, and the Association for the Sciences of Limnology and Oceanography. A Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Environmental Change and Society for 21 years, Leavitt explained to the audience that water quality is shaped by many factors—everything from sunlight and wind to city pollution and agricultural runoff. Basically, anything that finds its way into a lake can change the water, and not usually for the better. His research addresses how we figure out what’s harming our lakes, rivers, ponds, and wetlands, and how can we protect them more effectively.

In his talk, he dove into how his research has used satellites, fossils in lake mud, large-scale experiments, and more than 30 years of data from hundreds of lakes, ponds, and wetlands to piece together the story of our water and shed light on what our water quality was like before Treaties were signed, what it looks like today, and what threats lie ahead.

Michael Mensah is pursuing a PhD in biology, which he chose to do at the University of Regina to work with Dr. Kerri Finlay, biology professor and co-director of the Institute of Environmental Change and Society, along with Dr. Peter Leavitt.

Mensah’s energetic, three-minute presentation, Fresh Solutions for Salty Cows, closed out the research showcase, A Taste of Research: Enduring Discoveries.

Mensah explained that while we know that freshwater is essential for ranching in the Canadian Prairies, many farms rely on small ponds, either natural wetlands or dugouts, as a key water source for their livestock. These water sources often collect substances like sulphate, which can make the water too salty (much saltier than the ocean!), and harmful for cattle. High levels the salty water can even lead to death.

Fresh off a win at the National 3MT competition in Toronto, Mensah’s three-minute presentation focused on how his research uses natural mitigation techniques to reduce salt levels in agricultural ponds. He explained that he investigated around 40 different ponds that contained different salt levels - and studied environmental factors like soil, land use, and nearby vegetation. The result? That his research will help keep pond water safe for Saskatchewan’s livestock and improve the odds of a good year for ranchers.

Mensah’s next stop on the 3MT trail, is the North American 3MT final in St. Louis, Missouri on December 7. Best of luck!

University of Regina researchers understand the challenges of our times, and their commitment to long-term research is creating meaningful change for our community and beyond.

Built on knowledge, relationships, and years of data, U of R research addresses urgent issues like mental health, water quality, climate change, and Indigenous well-being. In this 50th anniversary year, U of R celebrates these lasting contributions and looks forward to a future of even stronger collaboration with communities, including Indigenous partners, to create impactful solutions.

Couldn’t make it to A Taste of Research? Watch the presentations here.

Long-term research is unpredictable, and its true value lies in the trust it builds, the empowerment it fosters, and the groundbreaking discoveries it enables.

In an age of quick answers, U of R’s research reminds us that the most transformative solutions take time—benefiting individuals, families, and communities for generations to come.

Banner photo: Dr. Aziz Douai, Dean of the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research, emceeing A Taste of Research. Photo Credit: University Communications.

About the University of Regina

2024 marks our 50th anniversary as an independent University (although our roots as Regina College date back more than a century!). As we celebrate our past, we work towards a future that is as limitless as the prairie horizon. We support the health and well-being of our 17,200 students and provide them with hands-on learning opportunities to develop career-ready graduates – more than 92,000 alumni enrich communities in Saskatchewan and around the globe. Our research enterprise has grown to 21 research centres and 9 Canada Research Chairs. Our campuses are on Treaties 4 and 6 - the territories of the nêhiyawak, Anihšināpēk, Dakota, Lakota, and Nakoda peoples, and the homeland of the Michif/Métis nation. We seek to grow our relationships with Indigenous communities to build a more inclusive future.

Let’s go far, together.

![[L-R] Michael Mensah, PhD Candidate (Biology) and Dr. Aziz Douai, Dean, Graduate Studies and Research, stand together for the first picture of Mensah as the winner of the 3MT Nationals.](https://www.uregina.ca/stories/2024/images/11-01/11-01-04-1600x1200.jpg)