|

What are the

differences between Basic Principles and Best

practices? As I looked into these two topics as

independent subject categories, I

discovered that the two tend to blur together. Today's

best practices are tomorrows basic

principles. Teaching

online is new to most educators. The short history of

online instruction is marked by pioneers who have

tried a

little of this with a little of that, a sort of trial

by fire, if you will.

What

follows are various opinions expressed in three

articles on what are the best practices

and principles of online education. The following

sources are particularly effective in simplifying

the issues in regard to successful practices. I have

only included excerpts from the articles. If

you would like to view the entire article, at the

end of each article is a link to the original

document. Also included

beneath each article is a link to a printer friendly

PDF version.

NOTE: A

more extensive selection of links to articles can be found under the Resources

link on left-hand menu bar.

*PDF Documents require the Adobe

Acrobat Reader

Best Practices and

principles of online education from Weber State

Best Practices

from University of Maryland study

Why

Encourage Student Interaction and Collaboration?

Best

Practices and principles of online education from Weber State

Weber

State University (WSU) faculty believe that the

following 18 points need to be included in any

successful Online Course:

1.

An online course should be based on the same

learning outcomes and demand the same rigor as a

traditional class. The identification of courses to

be taught online, the semesters in which to offer

them, and the assignment of instructors rest with

the academic department.

2.

Students should spend the same amount of time on an

online course as they do for a campus course. The

rule of 15 clock hours of class time per credit hour

should guide development of an online course.

3.

Online courses should reach the same learning

outcomes as traditional courses. Assessment of the

effectiveness of online offerings should be

conducted at the same time as and in a manner

consistent with departmental standards and practice

for traditional courses.

4.

Online faculty are responsible for identifying

copyrighted materials used in their courses and for

either citing that material appropriately or

obtaining written permission to use it in the web

environment in advance of coursework beginning.

5.

Discussions, chat, use of media (especially streamed

media) should all be chosen to be value-added to the

student.

6.

Every course should address the needs of students

with disabilities; boilerplate language can be

provided.

COURSE

COMPONENTS

7.

All online courses use the course template

(which includes navigation pathways and design

standards) developed by the WSU Online team and

modified by the experience of WSU Online faculty.

8.

Course content should be up-to-date at the beginning

of the term, with dates changed from term to term

and links updated.

9.

Because online courses are unique in being a form of

publication, experienced online faculty feel that

each course must reflect the highest professional

standards, including careful attention to such

fundamentals as spelling, grammar, and mechanics.

Comment:

Even though access to courses is restricted to

enrolled students, posting material to the world

wide web is a form of publication that reflects not

only on the individual faculty member but also on

the institution as a whole. Errors can be magnified

and multiplied in the online environment. The

standard stated here addresses the instructor’s

work. Each instructor may set and should articulate

his own standard for the level of editing expected

in student work.

If

the instructor views web assignments as written work

to be graded on mechanics as well as content, that

should be clearly stated. If the instructor is more

concerned that students make substantive content

contributions to an online discussion without

worrying about spelling (for instance), that too

should be clearly stated.

10.

When possible and when supportive of course

objectives, the course should draw on and

incorporate some of the vast information resources

available via the web.

11.

Instructors should feel free to use library

resources to the same extent for online courses as

they do in traditional classes.

12.

There should be task submissions for students with

substantive feedback on a regular basis, preferably

weekly.

13.

Online instructors should set and articulate clear

and realistic timelines for responding to students

and should adhere to them.

14.

Special efforts should be made to create and support

a learning community among online students who may

feel they are working in isolation.

15.

The course should use the richness of the electronic

medium to the fullest extent possible. Online

faculty should possess skills in word processing and

electronic communication at least equivalent to

those identified in the computer literacy

requirement for students.

16.

Course design should include appropriate orientation

about how the course is structured and how online

tools work.

17.

The online medium should be used for teaching and

learning activities. A syllabus and a set of online

tests do not constitute an online course.

18.

Every course should address academic honesty.

December

17, 2000

Weber

state article pdf

For

more information, the actual article is located at:

http://wsuonline.weber.edu/factraining/unit1/section1/guidelines.htm

#1.

Weber

State Article Question:

If you were to rate the top 3 points (out of the 18

points sited in the article), what would they be?

Explain why you feel these three points that you

selected are very important.

Back to Top

Best

practices from University of Maryland study

This

study examines how best practices in online

instruction are the same as, or different from, best

practices in face-to-face (F2F) instruction. The

book Effectiveness and Efficiency in Higher

Education for Adults [1]

summarizes some 20 years of research on best

practices in F2F instruction. The bases of

comparison are principles from the KS&G material

and from Chickering and Gamson’s “seven

principles for good practice in undergraduate

education” [2].

A reason for making these comparisons is that the

rapid growth of online instruction promises that

online instruction may become the largest source of

ongoing higher education. Not surprisingly, interest

in assessing the quality of online offerings has

also grown [3,

4,

5,

6].

The question is increasingly raised: Are

postsecondary institutions effectively “doing

their old job in a new way?” [7].

One way to answer that question is to analyze the

online instructional practices of faculty with the

aid of research on patterns of instruction,

face-to-face and online.

I.

PRINCIPLES OF BEST PRACTICE

The

book Effectiveness and Efficiency in Higher

Education for Adults [1]

(herein referred to as KS&G) undertakes just

such an analysis. The book surveys research of the

last 20 years, including meta-analyses of studies on

different principles of instruction, in search of

principles and practices with largest effect sizes

in explaining learning gains. Eight principles

emerge as a manageable set of principles meeting

this criterion. For each of the principles, case

studies are cited that apply each principle as

effective practices or strategies.

These

eight principles, though worded differently,

partially overlap and supplement the “seven

principles for good practice in undergraduate

education” [2]

(herein “C&G”).

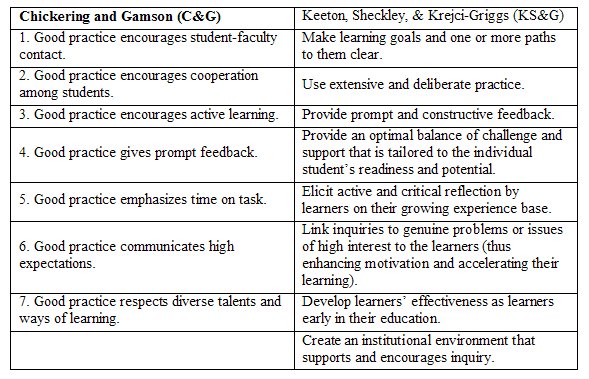

Table

1. Principles from C&G and from KS&G

A focus

on active learning is shared by the two analyses,

with KS&G making explicit the need for critical

thinking and including cooperation among students

and interaction between teacher and students as ways

to foster the active, critical reflection. Finally,

KS&G adds a focus on the institutional climate

or environmental press for inquiry as a key to best

practice.

II.

KEY FINDINGS

Key

findings of the study to date include the following:

- The individual instructor’s effectiveness in

applying the eight principles of KS&G is a

major factor in adult students’ learning and

persistence.

- Students need support additional to that of the

syllabus in understanding and pursuing the

learning objectives of a course or other

educational effort.

- Students in online courses expect faculty to be

more readily and promptly available at non-class

times than F2F students expect of faculty in

responding to the students’ communications.

- The most effective faculty actively use five or

more of the full array of instructional

principles so can they elicit the largest

learning effects.

- Faculty agreed that teaching well online is

more time-consuming than teaching F2F.

February 14,

2002

University of Maryland study pdf

For

more information, the actual article is located at:

http://www.sloan-c.org/publications/jaln/v8n2/v8n2_keeton.asp

#2. University

of Maryland Study Question:

Relate an experience you have had with an excellent

F2F instructor and respond to these two questions:

What made that instructor great? How would that

great instructor continue to be great in an online

environment?

Back to Top

Why Encourage Student Interaction and Collaboration?

Online course

communication tools enable students to interact with

course content, the instructor, and their peers outside of

the classroom. Students are given the opportunity to

negotiate the meaning of course content through

these interactions - creating the potential for a

deeper and longer lasting learning.

A virtual

learning community that provides support and sharing

among its members can be built through the integration of

online communication tools and course activities and

sustained through effective facilitation by the

instructor.

Fundamental principles of

constructivism support this view: learning is an

active process of constructing rather than acquiring

knowledge individuals learn through interaction with

their world individuals develop knowledge through

social interaction.

Changing

Roles in Online Learning Environments

Instructor

Role:

|

Face

to Face |

Online |

| -from lecturer

-from provider of answers

-from provider of content

-from total control of the teaching

environment

-from teacher-directed |

-to guide and resource

provider

-to expert questioner

-to designer of student learning

experiences

-to sharing with the student as a fellow

learner

-to learner centered |

Source:

Berge, Collins, 1996

Learner Role: towards

more collaborative/cooperative interaction with

peers

Learner

Role:

|

Face

to Face |

Online |

| -from

passive receptacles

-from memorizers of

facts

-from passive

learning |

-to

constructors of their own knowledge

-to problem-solvers

-to

active learning |

Source:

Berge, Collins, 1996

Certain

researchers suggest that a teaching method which

encapsulates collaboration and interaction would

likely work well within the framework of Internet

based distance education courses. In order to verify

how interaction and collaboration work between

students in distance education courses, we observed

and researched two undergraduate university courses

offered via the Internet. All communications were

text based and in asynchronous mode relying upon

e-mail, group discussions and hypertext navigation

to facilitate the collaborative work process. This

exploratory study has enabled us to identify some

problematic elements which can hamper collaboration

between distance education students. From these

results, we developed recommendations for ensuring

the success of collaborative assignments for future

Internet courses.

From what we have observed and analyzed,

the following recommendations have been compiled in

order to ensure optimal conditions for collaboration

via the Internet :

- Collaborative tasks should be an integral

element of the course design and should be

offered at regular intervals. As much as

possible, collaborative tasks have to be

evaluated on equal par with individual work.

- Distance learners should be encouraged to

construct learning together through meaningful

collaborative tasks which allow for pertinent

interaction. These collaborative tasks must be

based upon a constructivist approach rather than

a transmission type approach.

- Group composition has to be undertaken with

great care by attempting to match personal,

professional, cultural and academic backgrounds.

- It is necessary to indicate that collaboration

via the Internet did not work well within the

parameters of first year courses, which attracts

a multitude of students with diverse academic

backgrounds. Research has shown that

collaboration works well with a professional or

graduate course where the level of homogeneity

among students is much higher (Muffoletto,

1997).

March 3, 2000

Interaction and Collaboration pdf

For

more information, the two actual articles are located at:

http://www.cmu.edu/teaching/technology/bestpractices.html

http://ifets.ieee.org/periodical/vol_3_2000/d11.html

#3. Student Interaction and

Collaboration Question:

As a group in a threaded discussion, discus the

following problem: If you were an online instructor,

how would you get students to interact and

collaborate?

Back to Top

|